PILGRIMAGE TO THE HOLY LAND

(HUNTING FOR UNICORNS – PART 3)

Government bureaucrats and high-tech CEOs from around the world make their bi-annual pilgrimage to Silicon Valley – DALL-E Image Creator

As we’ve seen earlier, many factors probably contribute to a ‘healthy’ startup ecosystem. This article delves deeper into the private equity firms that fund high-growth companies. To do this, we rely on CB INSIGHTS’ list of 1,225 unicorns worldwide.

We looked specifically at startup ecosystems from 3 mid-size countries in terms of population and GDP:

- Canada

- The UK

- South Korea

Obviously, I am primarily interested in Canada. For comparison, I chose one country each from the middle powers in Europe and Asia with comparatively large numbers of high-growth companies (i.e. unicorns).

Who are these private equity firms, and where are they located?

Are the investors located in the same countries as their investee companies?

PROFILE OF CANADA’ S INVESTORS IN STARTUPS

There were 2 non-US, foreign-controlled private equity investors in Canadian unicorns, according to CB INUGHTS’ data. One was Australian, and another Irish. Clearly, we are relying almost exclusively on American private equity to fund high-growth businesses in Canada.

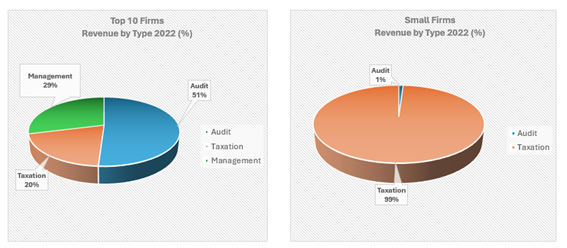

Of the 9 ‘private’ equity investments from Canadian firms, 2 were from Canada’s Business Development Bank, and 2 more from OMERS Ventures (Launched in 2011, OMERS Ventures is the venture capital arm of OMERS, the pension plan for Ontario’s municipal employees.)

There were only 3 private sector players in the private equity space for Canada’s unicorns. Georgian Partners of Toronto accounts for 3 of the 5 investments, with 2 small firms responsible for the other 2.

That certainly isn’t a ringing endorsement for home-grown, risk-taking private equity in Canada.

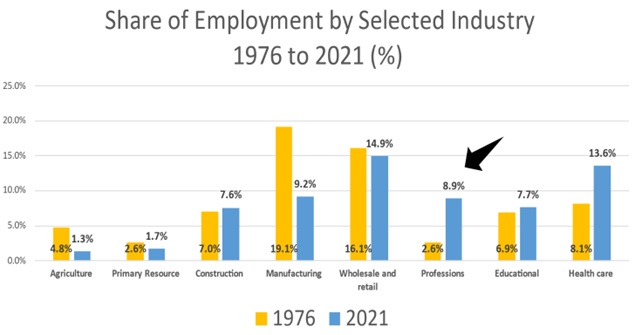

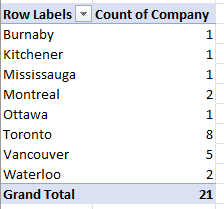

It’s also interesting to look at where unicorns are located:

Burnaby and Vancouver are really part of the Greater Vancouver ecosystem.

The Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) is a large urban region centred around Toronto, encompassing Waterloo, Brant and Haldimand in the west, Niagara to the south, Simcoe in the north, and Peterborough and Northumberland in the east . It is home to 10 million people, or over 60% of Ontario’s population.

Montreal seems under-represented with only 2 unicorns – although you might include Ottawa in the same ecosystem. These 2 cities are often seen as part of single Corridor:

The Montréal-Ottawa Corridor is a heavily populated region in both Ontario and Quebec. It is an east-west corridor with the eastern end being Greater Montréal and the western end being Ottawa-Gatineau. It is a sub-region of the Quebec City-Windsor Corridor. The Montréal-Ottawa Corridor includes the major centres of Montréal, Ottawa, Laval, Gatineau, and Cornwall and has a population of 5,700,000 (2020 estimate), comprising roughly 15% of Canada’s population.

The term was coined recently as the metropolitan areas of Greater Montréal and Ottawa-Gatineau continue to expand towards each other, thus decreasing the rural gap between them. Commuting between the cities continues to increase as the drive is usually less than 2 hours long (relatively very short for two large cities in Canada).

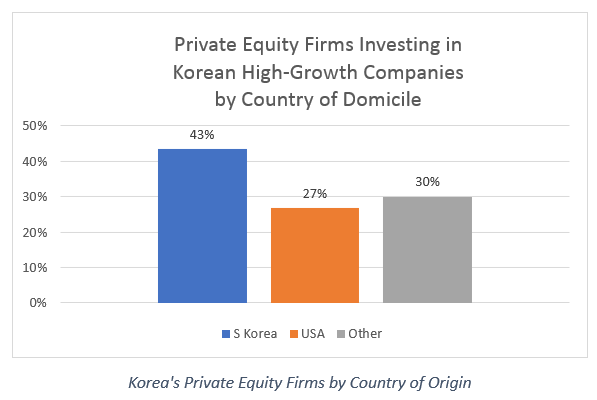

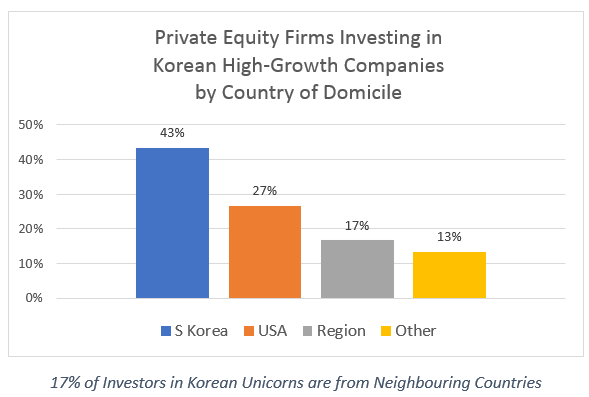

PROFILE OF KOREA’ S INVESTORS IN STARTUPS

One thing clearly stands out. The largest number of investors in Korean high-growth companies are based in Korea. What’s more, when we look at investors in the ‘other’ group, we find that most of these are neighbours.

In fact, between them, Korea and her regional neighbours account for 60% of private equity firms involved in high tech.

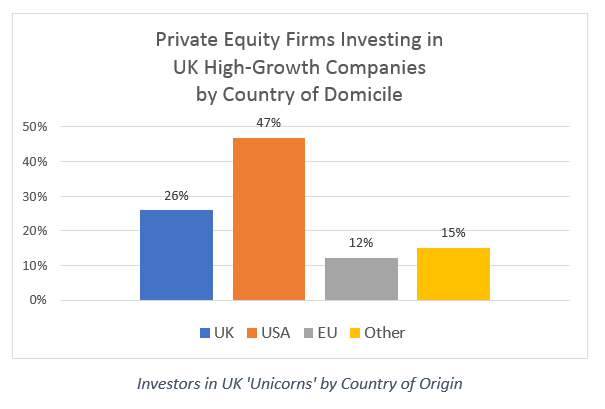

PROFILE OF UK’ S INVESTORS IN STARTUPS

The UK clearly has far more home-grown private equity than Canada. This may be because London has been a financial centre for the world, for more than a century. While the US dominates as it does in Canada, the UK also appears to benefit from proximity to the Eurozone.

In contrast with other startup hubs, Canadian private equity has little or no interest or expertise in high-growth technology companies. That may explain why Canadian governments of all stripes would like to encourage our investors to step up. However, we should ask ourselves whether our investors will ever develop much appetite for the type of risk that VCs worldwide are willing to take on. This may actually stem from a cultural difference between Canada’s billionaires[1] and those of Britain and the US.

In my view, Canadians have always been content to hide behind our border and use it to protect the interests of our largest companies (and the families that control them) from our pesky neighbours to the south. We prefer risk management to risk-taking.

I’m no different than other Canadians. I mostly invest in exchange-traded funds to get to diversification with my small portfolio. What’s more, they have much lower management fees.

My one foray into investing in high-growth companies wasn’t done to earn exceptional returns on high-risk investments. I was looking for introductions for technology companies seeking assistance claiming tax incentives for research and development.

While the BC Government may like to take credit for the fact that the second most important Canadian startup ecosystem is in Vancouver, I’m not so sure. Certainly, I don’t believe the BC Small Business Venture Capital Act has had that much effect. As stated in the first article there are two separate tracks for incentives under that program:

Two Investment Models

The BC program offers a choice of two different investment models:

- EBC MODEL – Eligible Business Corporations are individual companies located in BC that meet eligibility requirements

- VCC MODEL – Venture Capital Corporations are sole-purpose investment corporations that assemble mostly individual shareholders to invest in the same kind of companies

My experience with high-growth technology companies in Vancouver and the Lower Mainland of BC, is that US-based private equity is easier to find. That’s despite the $35-40 million our BC Government spends each year on tax credits to ‘sophisticated’ investors. About six or seven years ago, I went to Seattle to attend a meeting of angel investors. I was in the company of a lead investor from a Vancouver VCC who was trying to convince investors in Seattle to invest in our BC-based Venture Capital Corporation.

The problem was that neither of us was aware that – for Americans – a BC-based VCC would be considered a “PFIC” (a Passive Foreign Investment Company[1]).

[1] PFICs have significant disadvantages from a tax standpoint for US-based investors

While my hunch is that the VCC MODEL is of very limited value, I decided to test my hypothesis by subscribing to a service called “CRUNCHBASE”.

“Crunchbase is a company providing business information about private and public companies. Their content includes investment and funding information, founding members and individuals in leadership positions, mergers and acquisitions, news, and industry trends.” Wikipedia

While CB INSIGHTS’ data was useful, it was limited in terms of detail about investors other than the three leading investors in each “unicorn”. To determine who was providing funding to BC’s home-grown unicorns, I had to look to CRUNCHBASE.

That was a little easier than it sounds, since only five companies in British Columbia achieved unicorn status in the last dozen years or so.

None of these received any funding from a BC-based VCC. Most of the investment came from US-based VCs, while other investors included BDC Capital, Caisse De Despots, and private equity firms headquartered in other parts of Canada.

However, the one BC-based private equity firm made numerous investments in local BC-based companies and would certainly have been eligible to have taken advantage of the EBC Program. The largest company received family money and US-based VC funding. However, they did take advantage of the EBC Program to provide an employee share ownership incentive.

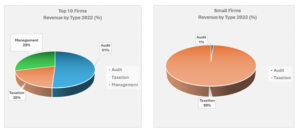

Based upon data from the Investment Capital Branch in BC, total investments raised to date by VCC’s was about $235 million in 2022. So while approximately 60% of funding is was raised using the VCC model, the most useful program for successful companies is probably the EBC program.

Where investor firms publish both investments and exits, the percentage of successful exits is 17%. This ratio has been consistent since Tech Coast Angels of California first reported their stats in 2007.

My own experience as an investor suggests to me that the services provided by venture capital corporations in terms of management and business experience to investee companies probably of little value. Their investments tend to be very small, and very early stage. The primary motivation may be to use investors’ money as bait for managers of these firms to sell consulting services to portfolio companies.

I believe that the Silicon Valley Playbook doesn’t work for startups outside of the US. We need to develop different strategies in BC. According to Alexandre Lazarow, partner in a Silicon Valley private Equity firm, the playbook doesn’t work in more isolated ecosystems like Canada’s. He believes that a better symbol for startups is a camel – not a unicorn.

“Thus far, companies in tech clusters like Silicon Valley have overshadowed a growing and impressive cohort of high-growth ventures that have taken root elsewhere. But that is changing. Successful start-ups on the frontier have critical lessons to teach us—indeed, their model may prove to be the most enduring.”[1]

[1] Beyond Silicon Valley – How start-ups succeed in unlikely places by Alex Lazarow