Canadians Log More Hours Than Other Countries But the Workforce is Less Productive. What Gives?

CLAUDE LAVOIE

PUBLISHED DECEMBER 12, 2023

Claude Lavoie was director-general of economic studies and policy analysis at the Department of Finance from 2008 to 2023. He has represented Canada at OECD meetings and has received many honours, including the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal.

Do Economists Have the Answers?

According to a December 2023 article in the GLOBE & MAIL. Claude Lavoie – director-general of economic studies and policy analysis at the Department of Finance from 2008 to 2023 –

“The Canadian work force is less productive because our firms invest less in technology and have less efficient business practices. As a share of the economy, Canada’s business investments in R&D, and on software, hardware and data are less than half those in the United States.

Our productivity problem is not new, and governments have tried to address it. It was noted in the early 1990s and has been a topic that most Liberal and Conservative budgets and economic growth plans have attempted to address since then.

So why have we not succeeded in turning things around? Because it is a hard nut to crack – economists do not have a good idea how to boost long-term growth – but also because some of the identified solutions are politically difficult. Year after year governments implement the same politically easy policies: giving subsidies, limiting environmental protections and lowering corporate taxes. This is despite evidence showing these measures are not very effective in raising productivity. Canada ranks ahead of all Group of Seven countries on the International Tax Competitiveness index and our subsidies to R&D are among the most generous. Yet our productivity continues to lag.

Analyses suggest that the key factors behind our poor productivity include a weaker competition environment and lower entrepreneurship skills. Competition increases productivity by driving low-productivity companies out of the market and encouraging entrepreneurs to pull out their “A” game. Canada needs to become feistier. However, our competition framework leaves a lot to be desired.”

“So why have we not succeeded in turning things around?

Because it is a hard nut to crack – economists do not have a good idea how to boost long-term growth”

This admission is a good start. But, in my view Claude Lavoie’s answer points to another problem.

“Competition increases productivity by driving low-productivity companies out of the market and encouraging entrepreneurs to pull out their “A” game. Canada needs to become feistier. However, our competition framework leaves a lot to be desired.”

His answer is straight out of an ECONOMICS 101 course. It’s what American lawyer and professor of law at the University of Connecticut School of Law James Kwak calls “Economism”.

“The problem, as the economist John Komlos puts it, is that “most students of Econ 101 do not continue to study economics so they are never even exposed to the more nuanced version of the discipline and are therefore indoctrinated for the rest of their lives.” As a result, writes the economist Noah Smith, “if economics majors leave their classes thinking that the theories they learned are mostly correct, they will make bad decisions in both business and politics.”

“Discussion of complex policy questions on the airwaves and the Internet is dominated not by careful economic research but by economism, which reduces complicated issues to a single, abstract model that is immune to facts. Its simple, catchy arguments are not published in peer-reviewed journals; they are generated by politically motivated think tanks, amplified by the media, repeated by lobbyists, and adopted by politicians as applause lines in stump speeches. Economism is Economics 101 retold as fable—as “narratives that lodge easily in the popular consciousness,” in Rodrik’s words.

He continues, “These fable-like narratives often have morals that can be formulated in catchy terms (for example, ‘taxation kills incentives’) and also sync up with clear political ideologies.” Economism is what you are left with if you learn the first-year models, forget that there are assumptions involved, and never get your hands dirty with real-world data. This is one case in which a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.”

– James Kwak – ECONOMISM: BAD ECONOMICS AND THE RISE OF INEQUALITY

Policy analysts like Mr. Lavoie may find it convenient to blame businesses for their lower ‘entrepreneurship skills.’ But that assumes our economy functions like it does in Economics 101.

Mr. Lavoie is right when he points out that:

“The Canadian work force is less productive because our firms invest less in technology and have less efficient business practices. As a share of the economy, Canada’s business investments in R&D, and on software, hardware and data are less than half those in the United States.”

But why don’t Canadian entrepreneurs invest in capital that would make us more productive?

The simple answer is that firms don’t invest – investors do!

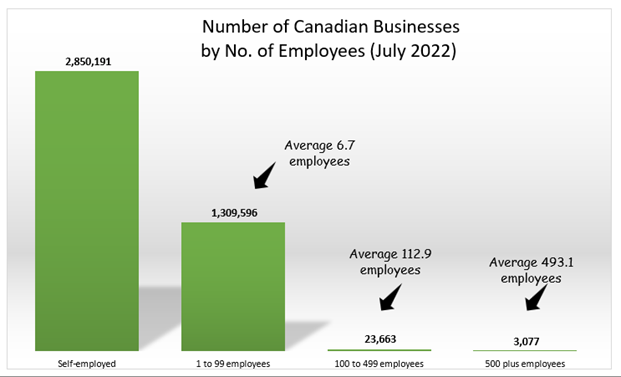

All markets—including Canada’s—are dominated by oligopolies. In Canada, there are 3 major cell phone providers, 3 in the US, and 4 in the UK. While most economists and policymakers decry the lack of competition in the Canadian economy, investment analysts tell us that Canada’s oligopolies offer great returns to Canadian investors.

Legendary investor Warren Buffett talks about exploiting ‘economic moats’ to earn extraordinary profits. Our American neighbours to the south are masters of protectionism. When Canadian companies are successful in breaching their defenses, American venture capitalists soon find a way to protect their vast markets from foreign competition. Most often by acquisition.

While this may work for Canadian entrepreneurs whose companies are acquired, government vanity projects like the Business Development Bank, the Export Development Corp. (“EDC”), or British Columbia’s Small Business Venture Capital Act, are pretty clearly a waste of resources.

Canada has a relatively tiny market. We cannot produce at scale to serve our own market when faced with competition from cheaper imports. So, since they don’t have a market that warrants producing at scale, our Canadian manufacturers must either export or be protected from cheaper imports.

Of course, if they choose to export they can count on the EDC to help them with that. (And that will have foreign competitors quaking with fear.)

But despite what business schools and policymakers would have us believe, almost every country is protective of its own markets. Economically powerful countries like the US preach free trade, but they don’t really practice it.

Perhaps we should question our naive faith in economics as taught in business schools and MBA programs. These days news organizations inevitably quote ‘experts’ from academia, the business professions, or officials with positions in public sector organizations whose raisons d’etre are clearly to tell us what our governments do for us!

Don’t get me wrong.

I believe that Mr. Lavoie is a rare thing among ‘policy experts’. He at least admits that “economists do not have a good idea how to boost long-term growth”.

[1] The Globe and Mail March 29, 2024