SUPERSIZE ME

Our Insatiable Appetite for Stuff (and Services)

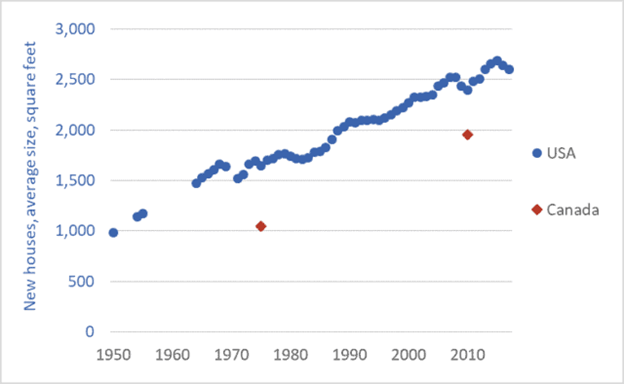

Average House Sizes 1950 to 2010

Average House Size 1950 to 2010 (SOURCE: Darrin Qualman’s Blog – 2018)

AI Summary by WORDTUNE

The average size of a newly constructed single-family detached home in the US is now 2,600 square feet and probably 2,200 in Canada. The average size of a new house has doubled since 1960.

Family sizes—as evidenced by fertility rates—have declined significantly in both countries since the 1950s, which is particularly worrying.

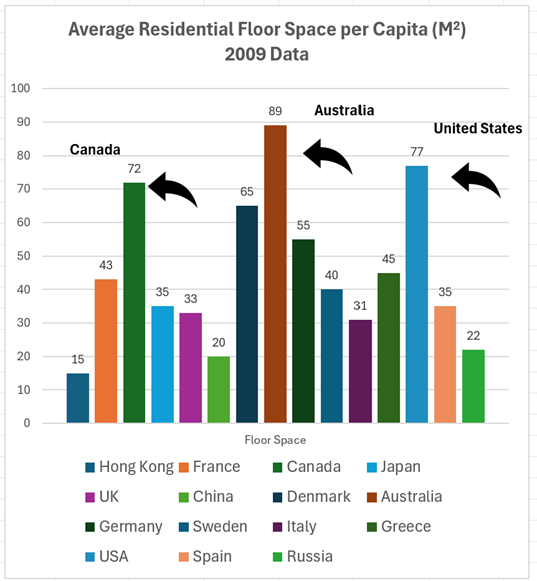

We like our personal space. Canadians and Americans have the greatest per-capita floor space in the world, with double the residential space of the average UK, Spanish, or Italian resident.

The biggest houses in the world require more energy to heat and cool, contribute to lower population densities and more sprawl, and are integral parts of high-consumption lifestyles. In Canada and the US, we are compounding our errors by making our houses bigger and more energy-inefficient.

Canadian debt now stands at a record $1.8 trillion, with $7,000 per year in interest payments for a hypothetical family of four[1]. Many families are paying a multiple of that amount, just in interest, and on top of that are principle payments.

Our ever-larger houses are filling the air with emissions, emptying our pockets of savings, filling up with consumer-economy clutter, and creating car-mandatory, unwalkable, unbikeable, unlovely neighborhoods.

Income inequality is manifest when some people have rooms in their homes they seldom visit, while others sleep outside in the cold.

[1] This article was written before massive increases in interest rates in 2022 and 2023

What Happened to the Entry-Level Car?

AI Summary by WORDTUNE

I last bought a new car about 10 years ago, and now I can’t find a new vehicle equipped with what I want for less than $25,000 to $30,000. What happened?

Consumers preferring bigger, fancier SUVs killed the entry-level car, said Robert Karwel, a senior manager at J.D. Power’s Canadian office.

In recent years, many companies have axed cheap starter cars, including the Chevrolet Spark, Fiat SOO, Ford Fiesta, Honda Fit, Hyundai Accent, Kia Rio, Nissan Micra and Toyota Yaris.

The Mitsubishi Mirage is still around, but the starting price has crept up. The Nissan Versa is the second-cheapest car, at $20,298 before taxes, freight and PDI.

The price of most carmakers’ cheapest cars has been climbing. Carmakers say buyers want features like heated seats and Apple CarPlay.

In 1990, the entry-level Civic ranged from $13,680 to $21,642, but in 2024, the starting price is $26,790.

Some carmakers have dropped manual transmissions from their base models because they said few were selling. But with increasing living costs all around, isn’t it likely there will be renewed demand for smaller starter cars?

Do millennials travel by air more frequently than baby boomers did at their age?

AI Summary by Microsoft Co-Pilot

Certainly! According to travel statistics, **Millennials** indeed travel more frequently by air compared to **Baby Boomers** when they were at a similar age¹. On average, Millennials embark on **5.6 trips** each year, which exceeds the travel frequency of Gen Z (4.4), Gen X (4.0), and Baby Boomers (3.5)¹. Additionally, in the US, Millennials travel approximately **35 days per year**, while Baby Boomers only take about **26 days** of vacation annually³. So, it’s safe to say that Millennials have a penchant for exploring the world more extensively!

Summary

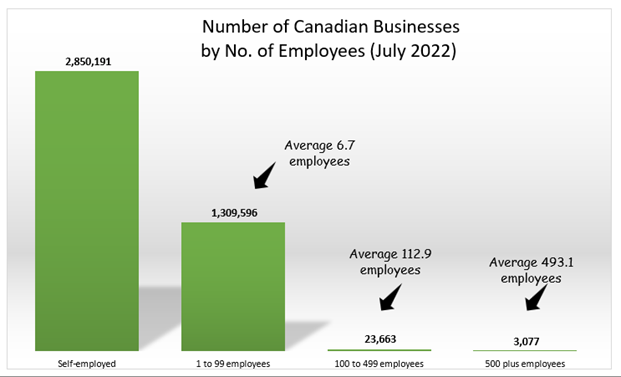

So, while households are getting smaller, houses are getting bigger. All of the other major expenditures we make in our lifetimes seem to be increasing in size as well.

Are increased house sizes improving our lives?

Do bigger cars and increased international air travel make our lives more meaningful – or do they just increase our carbon footprint?

We also spend more as a society on post-secondary education than we did in the past.

The rationale for investing in higher education is supposed to be greater ‘human capital’ and, hence, higher productivity. But that hasn’t happened in Canada.

It seems to have resulted mostly in increased immigration to feed the demands of our post-secondary education industry, greater competition for low-wage jobs, and more upward pressure on housing costs.

Millennials and subsequent generations are paying too much for too much living space, too much for bigger cars, too much for air travel, and too much for post-secondary education – not to mention too much for supporting their parents in retirement.

That will only get worse as increasing numbers of Canadians find employment in the public sector (from 25% in 2018 to 29% in 2022), with gold-plated pensions starting at age 65 or even earlier, and as new immigrants brought in to benefit our universities, re-settle their parents in this country putting further pressure on housing costs, healthcare, and income transfers to the elderly.