Canada’s Falling Productivity

(and what’s behind it)

THE PRODUCTIVITY-EDUCATION LINK

The conventional wisdom is that the more highly-educated the workforce, the greater the productivity should be. Most policy analysts and think tanks seem to reach the same conclusion.

In September of 2019, Gwilym Croucher[1] wrote in OXFORD BIBLIOGRAPHIES:

“Universities and colleges now demand a greater proportion of public and private resources and form a larger part of the economic life of most countries. Higher education contributes to growth and economic efficacy and, hence, the overall While few scholars dispute the productivity-augmenting power of education, and often research looks at the productivity of an economy, role of higher education alongside that of primary and secondary education, there remains much debate over the size of the contribution it makes to economic growth, economic efficiency, and, hence, to raising productivity overall.”

And…

“The relationship between higher education and improvements in overall productivity comes primarily from the contribution to economic growth of having a more skilled workforce. Universities, colleges, and other institutions of higher education are frequently asked to justify their effect on economic outcomes, especially where they receive significant public funding.”

According to a 2013 report by the US-based ECONOMIC ANALYSIS and RESEARCH NETWORK[1]:

- Overwhelmingly, high-wage states are states with a well-educated workforce. There is a clear and strong correlation between the educational attainment of a state’s workforce and median wages in the state.

- States can build a strong foundation for economic success and shared prosperity by investing in education. Providing expanded access to high quality education will not only expand economic opportunity for residents, but also likely do more to strengthen the overall state economy than anything else a state government can do.

[1] Associate Professor in Higher Education Policy and Management – University of Melbourne

[2] EARN is a nationwide network of research, policy, and advocacy organizations fighting, state by state, for an economy that works for everyone. (A Well-Educated Workforce Is Key to State Prosperity – August 22, 2013 by Noah Berger and Peter Fisher)

In 2008 the Canadian Institute for Research and Public Policy published a paper entitled:

Investing in Human Capital: Policy Priorities for Canada

“Human capital development has become a prominent issue of public policy. With the rise of the knowledge economy and rapid technological change, there is a growing demand for highly skilled, adaptable workers. Empirical studies consistently demonstrate that future growth in GDP is directly related to the knowledge and skills of the labour force.”

The problem here is that academic research institutes primarily represent the interests of academic researchers and universities.

The old adage is:

Canada is invariably at or near the top in terms of Education Level

What’s more, our commitment to education is increasing every year (see preceding chart).

Certainly, most Canadian governments buy into this conventional wisdom. However, in some cases, high productivity may be a bit of an ‘artifact’ that stems from the way that productivity is measured. A 2017 study by the Conference Board of Canada[1] highlighted this anomaly in productivity growth in Ireland in 2015:

“Ireland is the top-ranking jurisdiction on labour productivity growth by a huge margin. The country recorded real GDP growth of 26 percent in 2015. Because labour productivity measures the amount of GDP produced by each worker-hour in an economy, Ireland’s labour productivity growth skyrocketed to 22 per cent in 2015.Irish economists have a number of explanations for this jump, but generally agree it is something of a statistical artifact. The growth was likely due largely to a change in the way investment is calculated from GDP figures in European Union countries. A corporation that headquarters in a country now has its assets and intellectual property added to the country’s capital stock, and the growth in their value is now included in GDP. Irish capital stock increased by more than 30 per cent in 2015; there is speculation that a large number of corporations changed their domicile to Ireland, or that one of the many large multinationals that register there for tax purposes may have seen a large return on its assets. Ireland’s economy is not large compared to the size of some of the corporations, like Apple, that domicile there for tax purposes, so changes in their fortunes could have a huge impact on Irish national statistics. In addition to the changes in the capital stock, there was a jump in the number of aircraft purchased by lessors headquartered in Ireland. Even though these may never actually be in the country, they count towards GDP.”

Canada near the bottom in Productivity

So, what is behind Canada’s lagging productivity if it isn’t our lack of an innovation gene?

In my view, we should look at which countries – or provinces – have higher productivity levels and try to determine what characteristics they share.

In recent years the structure of the Canadian economy has changed. We need to ask ourselves:

What impacts have structural changes to the Canadian economy had on our productivity?

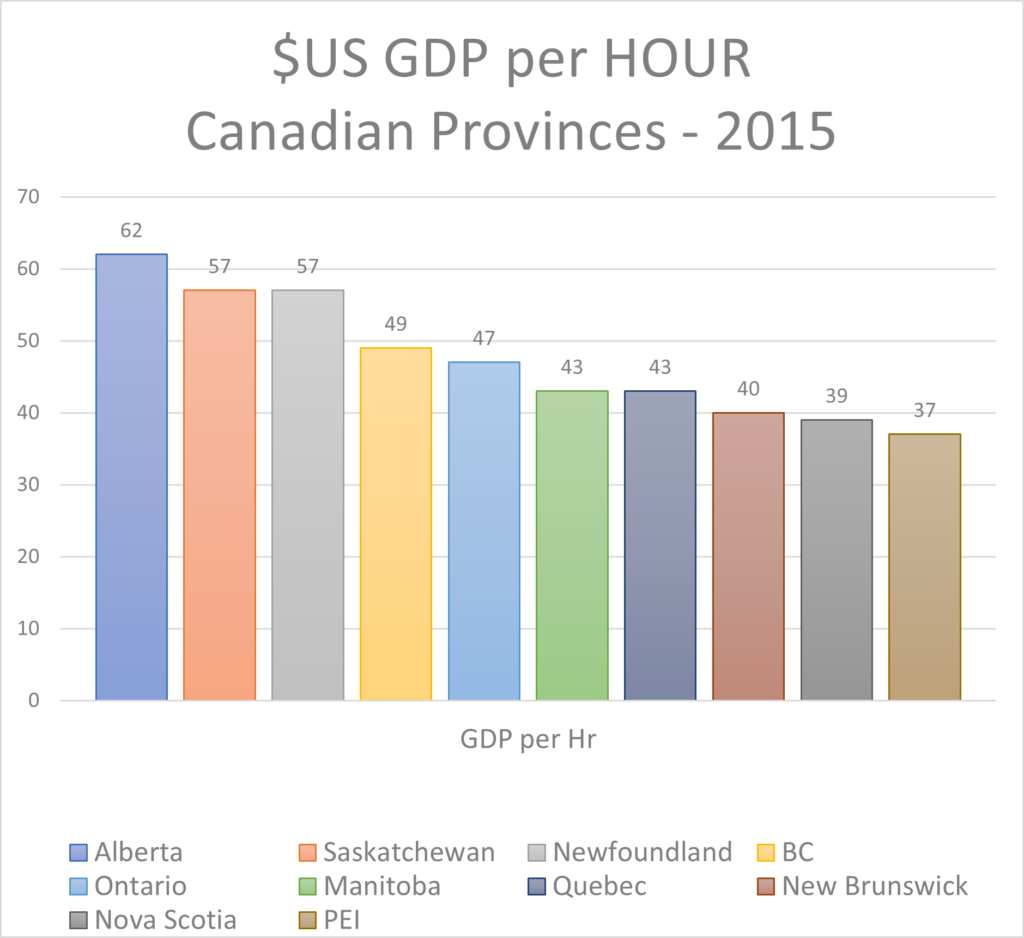

SOURCE: Statistics Canada and OECD 2015

Of course, first we need to understand how productivity is measured. According to that same (Conference Board of Canada) study:

“There is no silver bullet for improving productivity; many factors need examination.

Focusing on firm-specific factors, most provinces do well on the human capital component. Canadian workers, relative to their international peers, are well-educated and highly skilled. While there is room for improvement on adult literacy and numeracy skills, the quality of the labour force is not the driving force behind weak productivity growth.

When it comes to capital intensity (the amount of capital each worker has available, particularly machinery and equipment), provincial performance has been mixed. Not surprisingly, resource-intensive provinces are more capital-intensive. The capital stock per worker in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador is higher than the national average.”

RESOURCE EXTRACTION AND MANUFACTURING INDUSTRIES ARE CAPITAL INTENSIVE

Large manufacturing and processing concerns have significantly higher investments in capital equipment than service businesses. However, between 2006 and 2021, there has been a significant shift away from the ‘goods-producing sector’ towards services. (Source: Statistics Canada – Employment by industry, annual – Release date: 2022-01-07)

The one industry showing growth within the goods-producing sector has been construction. However, even in the construction industry, it could be argued that a significant component involves small, self-employed tradespeople with very little in the way of capital equipment.

Note that Norway has the highest productivity levels in world (GDP per hour worked). Norway’s largest industry is North Sea Oil:

“The petroleum sector is a key driver for the Norwegian economy. It is the country’s single largest industry. The sector accounts for 16% of GDP, 20% of total investments, 21% of state revenues, and 40% of total exports. Norway is the world´s 3rd largest exporter of natural gas, and the 13th largest exporter of oil. Indirectly, the petroleum sector contributes around 200,000 jobs throughout Norway. Norway’s oil production peaked in 2001 at 3.4 million barrels per day (bpd) and has declined to the current level of around 1.7 million bpd. Production is expected to remain relatively stable this year but will increase again once the large, new Johann Sverdrup field comes into production at the end of 2019.”[1]

[1]SOURCE: INTERNATIONAL TRADE ADMINISTRATION (ITA)

ITA is the premier resource and key partner for American companies competing in the global marketplace

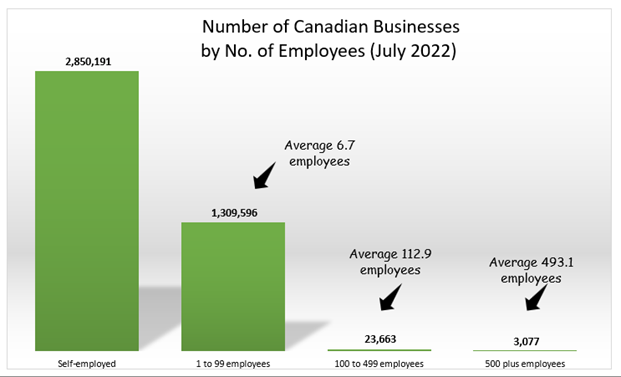

Excerpts from Statistical Video from SBA Canada – Youtube Video

In these 2 charts, we show the changes in employment in Canada by sector between 2006 and 2021. Virtually all the increases relate to health care, professional and technical services, construction, and public and administration. These occupations do provide generally higher incomes than other fields.

In other words, we have shed jobs in manufacturing and processing that involve significant investments in capital equipment and added jobs in professional and regulated services. Most of these new jobs involve very little capital equipment. It is large companies, with significant investments in machinery and equipment that tend to drive productivity levels.

In fact, we would argue that investments in higher education seem to correlate better with lower levels of productivity in OECD countries. It seems more likely that the self-interest of our colleges and universities is what’s behind our world-leading investment in higher education.

Given this situation, it isn’t surprising that young Canadians choose to study for careers in the regulated professions (including education). That may result in higher incomes for graduates – but it won’t result in higher productivity.

SOURCE: Statistics Canada and OECD 2015

From this chart, we can see that Alberta, Saskatchewan, Newfoundland, and BC have the highest productivity levels in the country. So, what do they have in common?

SOURCE: Statistics Canada (Labour force characteristics by industry, annual)

Not surprisingly, the 4 provinces with the highest productivity rates also have more people employed in the oil & gas and mining sectors.

We believe that policymakers should study what’s happening in higher education down south. Enrolment levels in the US are falling.

Employers there are beginning to question the conventional wisdom, pushed by the ‘higher education industry’. The Harvard Business School seems to be bucking the trend of decreasing enrolments. Maybe policymakers should consider looking to their Future of Work initiative.

Do we want to invest more in our energy sector?

Do we want to reduce reliance on outsourcing manufacturing and processing to China and other low-cost jurisdictions?

Do we want to reconsider whether universities are well-suited for vocational training?

Do we want to reconsider the proliferation of regulated professions and the extent to which their monopoly protection serves the public interest?