BEWARE THE WALKING DEAD:

Tax Incentives for Angel Investors

Twenty-five years ago, the government of British Columbia introduced the SMALL BUSINESS VENTURE CAPITAL ACT. After a quarter of a century, it’s probably time that we reflected on how effective that program has been. The BC venture capital credit is the granddaddy of all the provincial credits. In recent years, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba have all followed suit in recent years[1].

In 2013, I succumbed and invested in a Venture Capital Corporation based in Vancouver. Ten years later, the company tells me my investment is worth almost twice the original cost. But it’s going to be hard to get my money out. Since the company was formed in 2011, we’ve invested in 45 technology startups and have managed to cash in on only 6. The remaining companies are what angel investors call “zombies” or “the walking dead.”

[1] Though Alberta eliminated theirs only a couple of years after launching it.

So, let’s start with a definition of what is meant by those pejorative terms:

“In the context of early-stage investments and startups, the terms “zombies” or the “walking dead” are used to describe companies that have received initial investment but are struggling to grow, innovate, or achieve significant milestones. These companies may still be operating, but they are not showing signs of progress or potential for a successful exit (e.g., through acquisition or an initial public offering). Instead, they continue to “walk” or operate in a state of uncertainty, often consuming resources without generating substantial returns for investors.

Key characteristics of “zombie” or “walking dead” startups may include:

Lack of Growth: These companies may have reached a plateau in terms of customer acquisition, revenue, or market expansion. They struggle to achieve the rapid growth typically expected from early-stage startups.

Sustainability Issues: They may have difficulty sustaining their operations, relying on continuous funding rounds to stay afloat without a clear path to profitability.

Product-Market Fit: They may have failed to find a product-market fit or have difficulty retaining customers due to issues with their product or business model.

Management Challenges: Problems with leadership, strategy, or execution can hinder their progress.

Investor Uncertainty: Investors in these companies often face uncertainty about the likelihood of a return on their investment. They may find it challenging to exit their investments or see a return on capital.

Investors refer to such companies as “zombies” or the “walking dead” to emphasize the need for a change in strategy, leadership, or the potential need to wind down the company. In some cases, additional funding may be provided to try to revive the company, but these situations can be challenging for both investors and the startup’s founders.” – CHAT GPT

So, how common is this situation among the sixty-eight Venture Capital Corporations listed on the Province of British Columbia’s Register of Venture Capital Corporations?

Since the register doesn’t disclose exits, I had to buy a subscription to CRUNCHBASE.COM to get a sense of how these companies have done.

Of the 68 companies listed, I only found 239 investments and 40 exits. One single company accounted for 33.5% of those investments (80) and exactly ½ of the exits. In my view, that seems like another policy failure on the part of the provincial government. Rather than economic development, the program sounds more like a ‘vanity project’ than anything else. Like many government programs, it let anyone who was interested know what their government was doing for them.

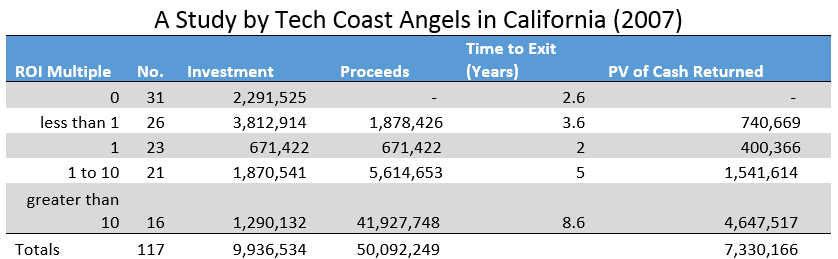

Back in 2007 – long before Aileen Lee of Cowboy Ventures came up with the term ‘unicorn’ to describe billion-dollar startups in 2013 – Tech Coast Angels out of California released a study showing actual returns on a portfolio of 117 early-stage investments.

Interestingly, even though Tech Coast Angels made massive returns on 16 of their investments, the net present value of their returns was slightly negative[1]. What’s more, in their case, they had at least some return on 73.5% of their investments. That compares with British Columbia VCCs – or at least those that reported their results – of them only 17% realized exits. The remaining investments were “unexitable”. That even makes it hard for investors to claim a tax loss.

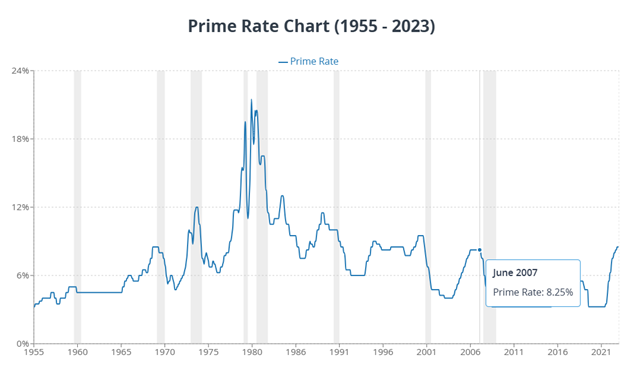

In 2007 Tech Coast Angels were playing in a much higher interest-rate environment:

[1] Using Tech Coast Angels’ risk-based discount rate of 24.3%. Note that the discount rate used is a key determinant of present value. If we used the average long-term return on US stock markets since about 1800 of 6.5% to 7.0%, the present value would be very positive.

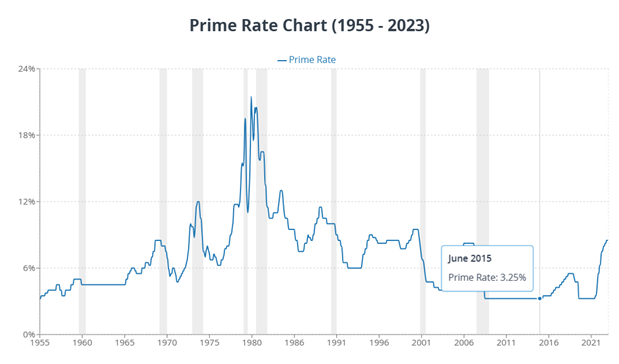

After the 2008 meltdown, VCCs in British Columbia enjoyed an extended very low interest rate environment for at least seven years.

Using Tech Coast Angels’ risk-based discount rate of 24.3%. Note that the discount rate used is a key determinant of present value. If we used the average long-term return on US stock markets since about 1800 of 6.5% to 7.0%, the present value would be very positive.

The abysmal returns for BC’s venture capital corporations clearly illustrate the ineffectiveness of the program. Perhaps the most significant factor in their poor performance is the structure of BC’s VCC program. Investors are prohibited from using convertible debt as a vehicle. That is the preferred option for Silicon Valley investors.

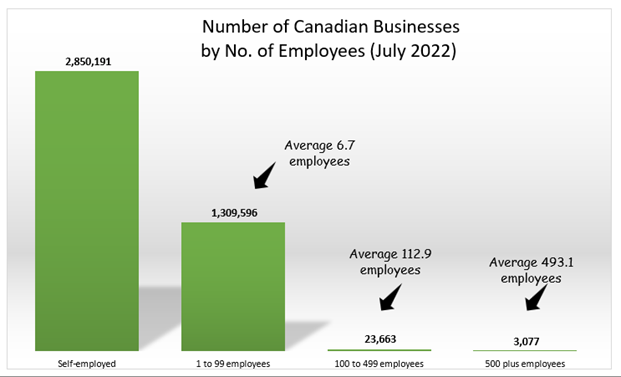

Consequently, most VCCs are saddled with investments in small, private corporations that may be impossible to sell and have little or no value. On average, they appear likely to represent about 87.5% of their portfolios.